A medal, a mantra and a movement: “Video—Couldn’t Live Without It!” landed like thunder.

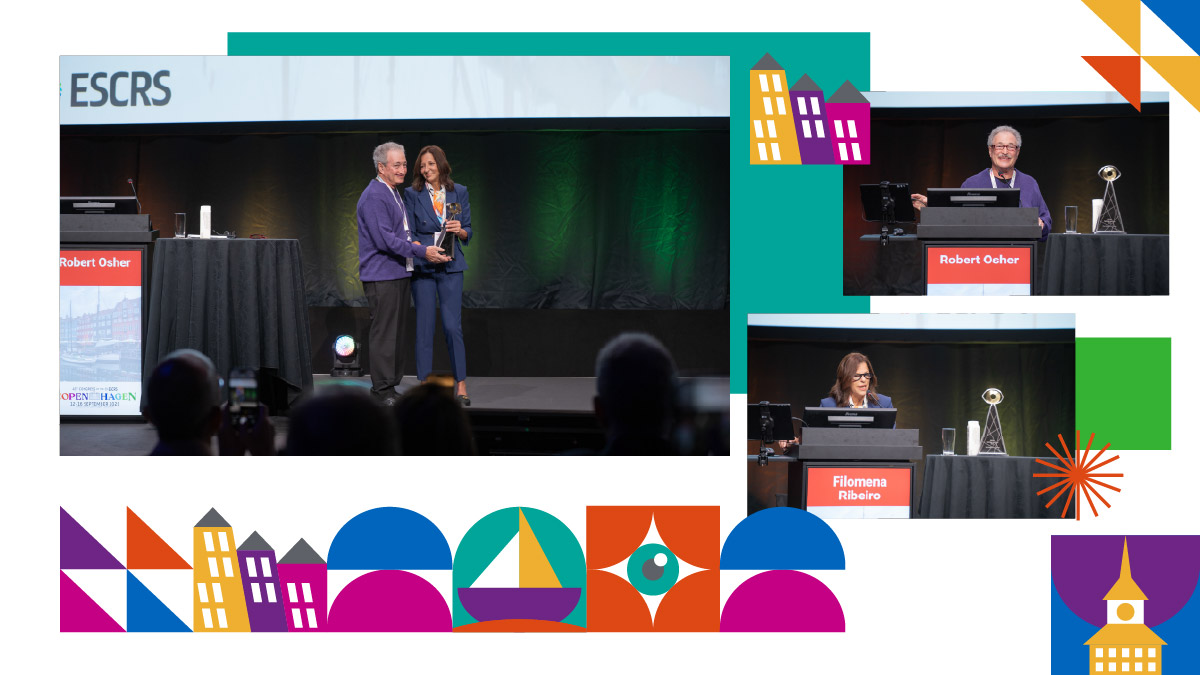

On Day 3 of ESCRS 2025 in Copenhagen, the packed Bella Center hushed as ESCRS President Prof. Filomena Ribeiro (Portugal) stepped forward to present one of the society’s highest honors: the Heritage Medal.

This year, the award went to a man synonymous with surgical teaching, humility and storytelling: Dr. Robert Osher (United States). His lecture, titled Video – Couldn’t Live Without It!, promised less of a technical masterclass and more of a love letter to the art of teaching through moving images.

READ MORE: Opening Ceremony & Binkhorst Medal Lecture: Vikings, Vision and a Short-Sighted World

A career in frames

Dr. Osher opened with disarming honesty. “I’m not sure you’re going to be clapping at the end of this lecture. There’s not much education in this lecture, but I will tell you that I’m so honored to be here.”

For him, this was not a lecture in the traditional sense but a personal narrative spanning fifty years of ophthalmic surgery—and fifty years of video.

He traced his fascination back to 1973, while working with neuro-ophthalmologist Dr. Lawton Smith (1929-2011) at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute (Florida, United States). Even then, he sensed there had to be “a better way to learn than by listening about internuclear ophthalmoplegia or by studying photographs in a book.”

The better way would come soon enough: the VHS machine. Purchased originally to show Peter Pan to his children, it transformed his teaching. “Video. Wow. It was a completely new way to communicate,” he recalled. From patient education videos to early surgeon tutorials, Dr. Osher quickly realized the lens of a camera could reach where textbooks could not.

Teaching through mistakes

One of the lecture’s recurring themes was Dr. Osher’s fearless embrace of imperfection. In 1981, when he introduced the first video symposium at AAO, he did the unthinkable: he showed his complications.

“I dared to show my complications, of which I had many,” he said with a wry smile. It wasn’t a strategy for popularity—“I wasn’t invited back for 10 years,” he admitted—but it was a turning point for the culture of surgical teaching. Surgeons could finally learn from what went wrong, not just polished highlights.

“The audience loved to watch me suffer,” he joked. But in truth, they loved to learn.

The birth of a video journal

Out of this realization grew one of Dr. Osher’s greatest legacies: the Video Journal of Cataract, Refractive, and Glaucoma Surgery (VJCRGS). Founded in the early 1980s, it was the first video journal in medicine.

“The first video journal in medicine where I could invite surgeons to record and send a video which I would edit and publish showing new techniques and technologies,” he said. The idea was deceptively simple: surgeons could watch with “beer and pretzels in the comfort of his or her living room.”

Distribution was no small task in the VHS era. Dr. Osher credited partnerships with companies like Alcon and AMO for hand-carrying tapes “around the planet as more and more countries acquired video players.”

And in those videos, he pushed boundaries: combining phaco with astigmatic keratotomy in 1985 (“the very first refractive cataract surgery,” as Dr. Richard Lindstrom later described), or clear lensectomy for hyperopia—radical, controversial, but captured forever on tape.

READ MORE: The Lean, Green Sophi Phaco Machine

Innovator, storyteller (and smuggler?)

Dr. Osher shared tales that balanced gravity with humor. He confessed to “smuggling” capsular tension rings and prosthetic irides into the United States after seeing them in Europe. He spoke of dragging giant ¾-inch tape machines across the globe, only to land in Peru where “they didn’t have a single ¾-inch player in the entire country.”

He celebrated colleagues who pushed the field forward on film: Dr. Charles Kelman’s (1930-2004) phacoemulsification, Dr. Kunihiro Nagahara’s (Japan) Phaco Chop technique, Dr. Howard Gimbel’s (Canada) optic capture, Prof. Graham Barrett’s (Australia) single-piece IOL, Dr. Robert Cionni’s (United States) modified capsular tension rings (CTR). Through video, their breakthroughs became immortalized, accessible and endlessly replayable.

Lessons from illness

The lecture turned poignant when Dr. Osher shared a personal health scare: the discovery of a malignant kidney tumor. “An MRI for some mild unrelated lumbar symptoms shook up my universe,” he said.

From that ordeal, his perspective crystallized. “Hug your kids and your spouse. Tell them often how much you love them, because there are no guarantees that you’ll be able to tomorrow.”

It was a reminder that behind the lights, cameras and surgical milestones, the real legacy is family and connection.

A global impact

For over 40 years, Dr. Osher has edited the VJCRGS, giving it away free of charge, without advertisements, to cataract societies worldwide. “Because of video, we are all better, more knowledgeable and more skilled ophthalmic surgeons,” he reflected.

The lecture became a sweeping tribute not only to video but to the global community it built—a community that laughs together, learns together and improves together.

Looking ahead: virtual reality

As the lecture wound down, Dr. Osher teased the next frontier. “After video comes virtual reality,” he said with a grin.

For the past six months, he has been working with a startup called VirtuaLens, creating immersive tools for patient education. Imagine slipping on goggles to “see every different lens in six different settings: kitchen, golf course, driving.”

If video transformed how surgeons learned, VR may transform how patients choose.

READ MORE: Smart Tech in Refractive Surgery

Closing applause

By the end, there was no doubt about applause. The audience rose, honoring a surgeon, teacher and pioneer who turned VHS tapes into a universal language.

“From one small idea and thousands of videos later, it’s been so satisfying to teach and to learn from each of my dear friends at ESCRS,” Dr. Osher concluded. “Because of video, we are all better…and I’m glad to have played a small role in this wonderful journey.”

This was not just a medal ceremony. It was a living chronicle of how one man, armed with a camera, changed the face of surgical education forever.

Editor’s Note: The 43rd Congress of the European Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgeons (ESCRS 2025) is being held from 12-16 September in Copenhagen, Denmark. Reporting for this story took place during the event. This content is intended exclusively for healthcare professionals. It is not intended for the general public. Products or therapies discussed may not be registered or approved in all jurisdictions, including Singapore.