A philosopher-ethicist reminds ophthalmologists that while AI can assist the eye, it must never replace the mind behind it.

From punch-card looms to AI-powered diagnostic tools, technological innovation has always carried a double edge: immense promise paired with hidden risks.

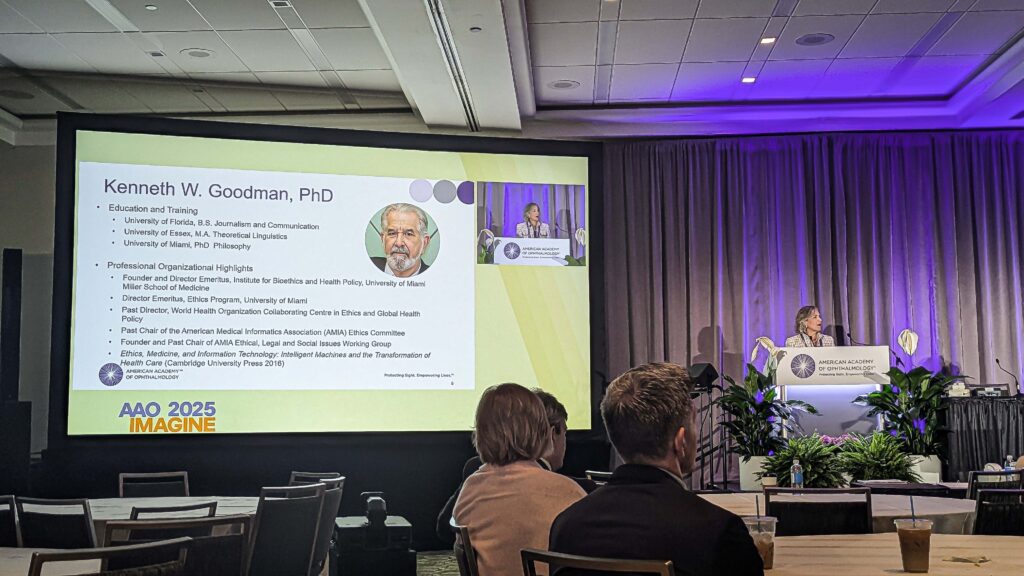

On Day 2 at the American Academy of Ophthalmology Annual Meeting 2025 (AAO 2025), Dr. Kenneth Goodman (USA) took the audience on a journey through computing history to show how optimism often outpaces ethical reflection…and why ophthalmology mustn’t fall in the same trap.

His talk explored the rise of AI in medicine, the challenges of trust and the critical need for transparency, governance and human accountability in a world where machines are learning more than ever.

When machines learn too much

To make his point, Dr. Goodman took the audience on a time-warp: from punch-card looms to 5 MB hard drives that required back braces to lift. His slideshow looked like an archeological dig through computing history, each image revealing the same familiar pattern: boundless optimism greeting every new gadget.

“Just an information device,” he said, referring to the punch-card machine later repurposed by Nazi Germany to track citizens. “What could possibly go wrong?”

The mix of humor and unease framed his warning: technological marvels often come with moral blind spots. From the Jacquard loom to the first Apple Mac in 1984, every innovation promised progress–and every era had to relearn responsibility.

The challenge for ophthalmology, he argued, isn’t to halt innovation but to remember that the proper use of any machine is rarely obvious from the outside.

READ MORE: Subspecialty Day at AAO 2025: Lenticules, Award Lectures and New Technology in Focus

The hard problem of trust

Fast-forward to today’s intelligent tools. AI reads scans, drafts notes and even writes messages that sound empathetic. But what happens when the software starts to sound too human?

When it becomes irrational for humans or clinicians to question an algorithm, we risk falling into what Dr. Goodman called “harmful epistemic dependence.” When doctors feel outmatched, they may simply comply with AI rather than challenge it.

If a system is more accurate than humans, reliable, bias-free, transparent and socially responsible—a so-called parfait system—then who dares to challenge it? The dangers of AI, Dr. Goodman warned, is not that it will make mistakes, but that humans will stop asking whether it has.

And even the most “perfect” code still depends on imperfect people. Dr. Goodman showed slides of “computer shops in the Philippines” where low-paid workers label data, so AI systems can function. AI, he noted, remains a tool made by and for humans…and ethical accountability cannot be outsourced.

The AI promise (and its catch)

AI’s potential is enormous, but Dr. Goodman noted a hidden socioeconomic catch. The technology is only as good as the access people have to it. In other words, systems may work well, but access is far from equal.

He called for a shift in the healthcare AI business model. Profit and intellectual property aren’t the villains here, but they can’t be the only values driving patient-care technology.

His vision is pragmatic: develop and deploy AI ethically and equitably, ensuring that better tools don’t widen the gap between those who can afford innovation and those who cannot.

Learning to look under

As artificial intelligence grows rapidly, Dr. Goodman urged physicians to push for transparency. “Does anybody here know any software, let alone AI software, let alone the backpropagation algorithms that are used as the basis for a lot of this?” he asked.

He argued that physicians should have as much right to inspect the codes that guide patient decisions as institutional review boards have to inspect drug-trial molecules. “We need to see your code,” he emphasized.

That insistence on “looking under the hood” comes from his career in bioethics and biochemical informatics. The goal is not to ban machines, but to make them morally intelligible.

Ophthalmologists, he stressed, should not surrender their intellectual curiosity at the door.

READ MORE: From Medicare Math to Musical Mastery: Inside AAO 2025’s Opening Session

Governance and the human element

Dr. Goodman’s closing slides were a to-do-list worthy of any morning rounds:

- Conduct more safety and outcomes research

- Manage intellectual property issues

- Manage privacy issues

- Preserve data among physicians

- Build governance and oversight frameworks

- Educate and don’t just train.

As he put it, “Do not stop ophthalmologists from being able to share what they learned with their colleagues. No business plan ought to require that.”

He also noted ongoing collaboration with the World Health Organization on AI ethics standards and to the Academy’s own proactive ethics committee that can be found online.

Pages you can go to:

- AAO statement on Artificial Intelligence

- Rescinded White House “Blueprint for an AI bill of rights”

- World Health Organization, “Ethics and governance of artificial intelligence for health”

The takeaway

In one of the lecture’s striking moments, Dr. Goodman asked, “How many of you, at the end of the day, have gone home and worried about a patient?” Then came a pointed reminder: “The computer sounds like it cares about your patients, but it’s not worrying about them.”

What we can learn from Dr. Goodman’s talk is that no computer can replace physicians. It’s the knowledge, the care, the heart—and the five senses—that humans bring, which no technology can replicate.

Editor’s Note: The American Academy of Ophthalmology Annual Meeting 2025 (AAO 2025) is being held on 17-20 October 2025, in Orlando, Florida. Reporting for this story took place during the event. This content is intended exclusively for healthcare professionals. It is not intended for the general public. Products or therapies discussed may not be registered or approved in all jurisdictions, including Singapore.